An iconic Greek Revival Row house pair in the Longfellow Square neighborhood.

A look at John Neal and the house he built for himself and his family.

Author’s Note: I had originally planned on an “In Focus” on John Neal but, to be honest, his entry at Wikipedia is so comprehensive that I cannot begin to match it. So, I will look at his house and other real estate related items. I do recommend reading the Wiki. John Neal was a complex man who followed many paths. His is quite the story.

John Neal was born, 12 hours after his sister Rachel, in Portland in 1793. His father, also named John, was the town schoolmaster. He died in 1794, possibly of ‘throat distemper’, at the age of 30. His mother, Rachel, was a descendent of the Winslow family. After her husbands death, Rachel Neal opened a private school which she ran for over 30 years.

The Portland that John Neal was born into was mostly recovered from effects of the war and was starting to capture the attention of the rising merchant/shipping class that would become a dominant force in the city in the decades to come. It was into this merchant world that John entered at the age of 12 when, according to his auto-biography, his “education was complete” and he began working as a clerk in the store of James Neal, his uncle. The store was on Exchange Street. This would begin John Neal’s lifelong connection to this street.

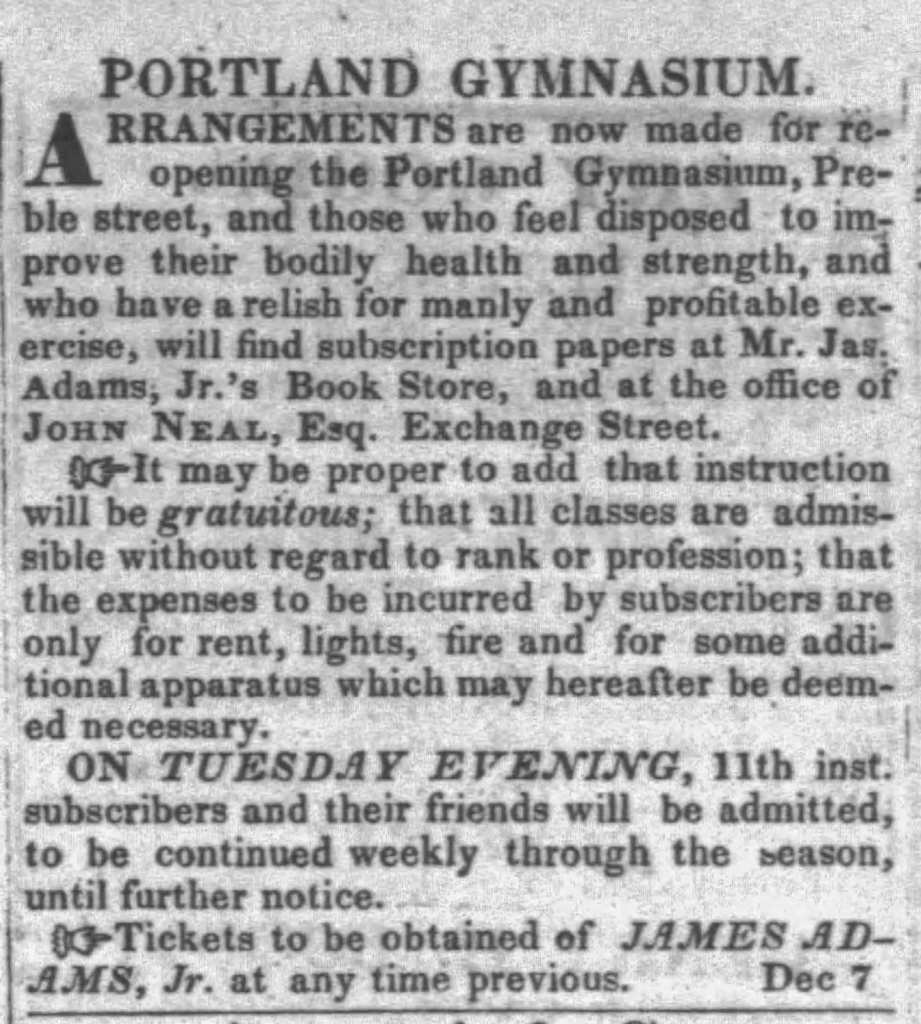

John Neal spent over a decade in Portsmouth, Boston, Baltimore, London before returning to Portland in 1827. In 1828 he opened a law office on Exchange Street, a gymnasium, Maine’s first, and married Eleanor Hall. John & Eleanor were second cousins & descendants of Hatevil Hall. The couple had 5 children with an 11 year gap between the third and 4th. One child, Eleanor, died in infancy. They lived on Middle Street while preparing to build their own home.

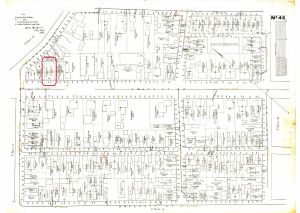

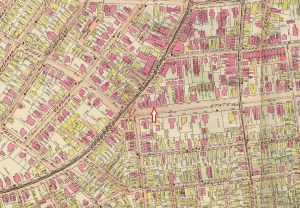

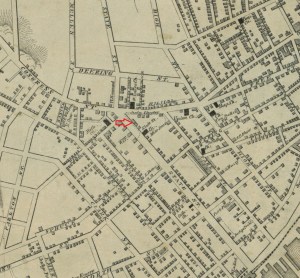

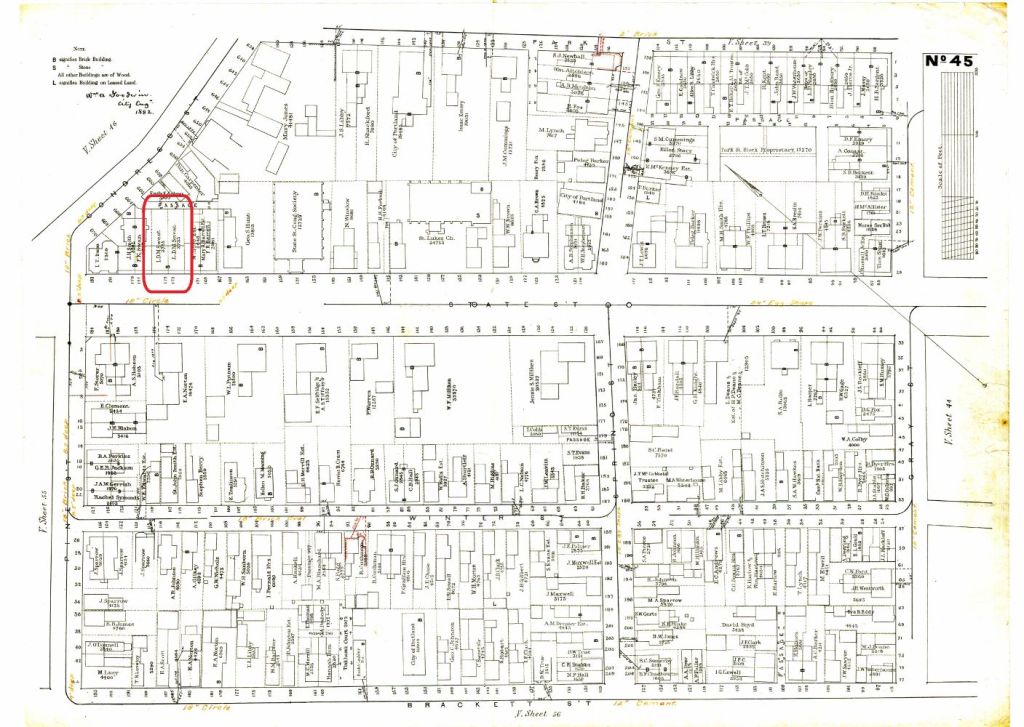

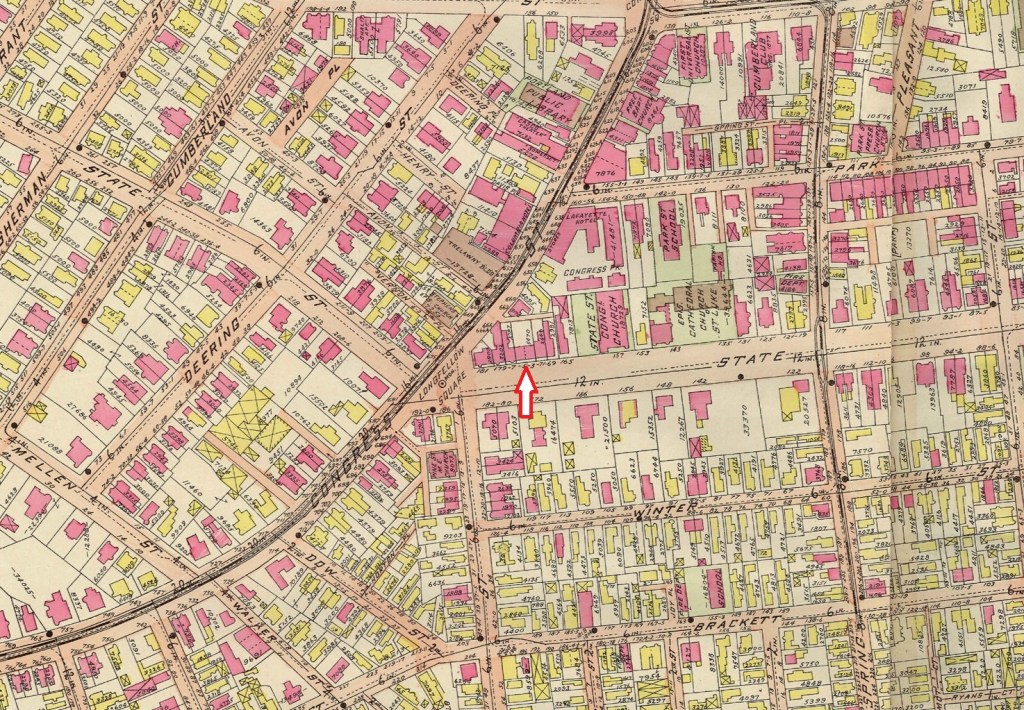

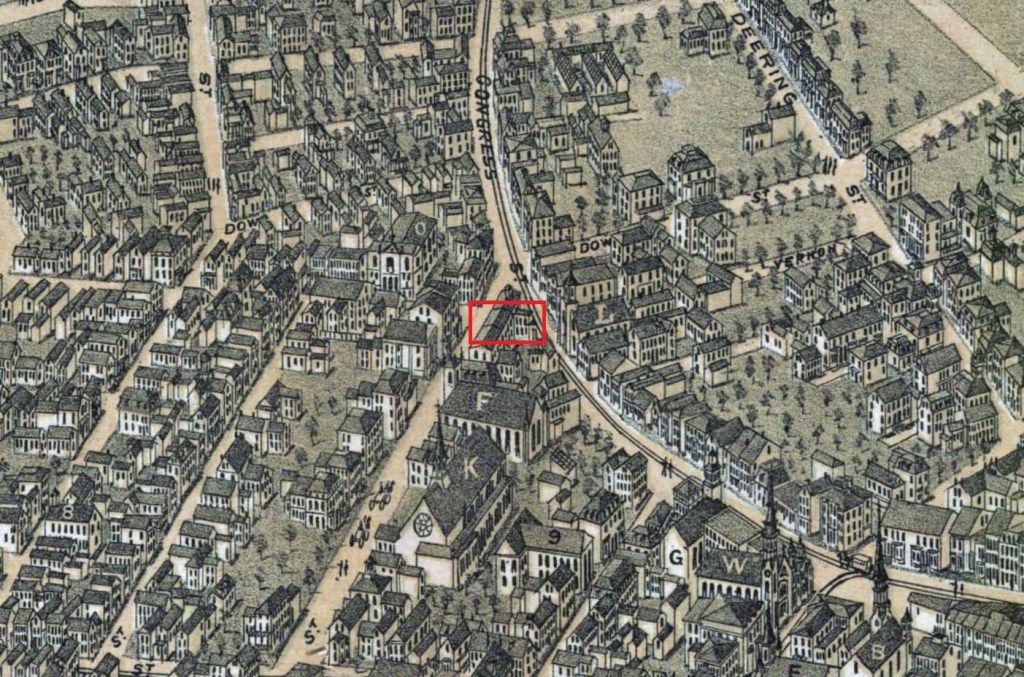

Much of state Street was still unbuilt in the 1830s. The blocks nearest to the waterfront had been built up first and houses were sprouting up at random spots but, most of the land abutting the street was still open space. It was here, near the intersection of Congress Street, that John and Eleanor Neal choose to build. There is no deed of purchase so when and from whom the land came, along with how much the Neals paid. is not known.

173-175 State Street measures 108′ on the street, 54′ wide for each unit, and 40′ deep. They are 4 stories with and attic which, I believe, is not currently inhabited. The floorplan is ‘standard’ row house plan with halls and stairs/elevators along the shared wall side. The stylistic program is a severe Greek Revival that was penned by Neal himself. There is minimal projecting detail outside of the portals, the strong belt-line, window sills, and the oddly proportioned hoods over said windows. The second floor windows above the portals are set into the wall. The granite is of a very fine grain that could be, at first glance, taken for precast concrete.

Granite

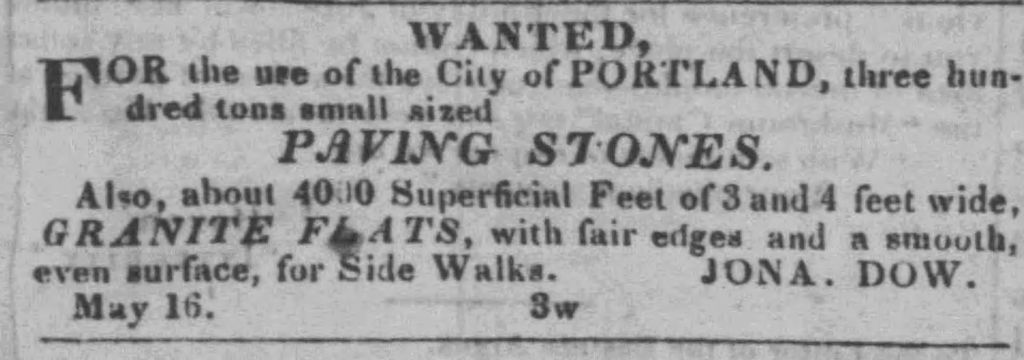

Although used in municipal, commercial, & infrastructure work, granite was, and still is, an uncommon material for residential construction outside of foundations. Francis Cook used it for the front of his house on lower State Street but that was almost a decade after John Neal used it here. Although not quarried locally, granite was being taken from surface exposures in Maine by the late 18th century. By the time of our story, it was being quarried commercially to an extent that, in 1832, the newly minted city of Portland advertised for granite ‘flats’ with “fair edges and a smooth even surface, for sidewalks”.

That he could have found the stone needed for his home via contacts within Portland seems likely, but John Neal, and a couple of associates, had bigger plans.

In early June of 1835, John Neal purchased a half-ownership of a piece of land in North Yarmouth. Along with the land, came the rights to quarry granite from the site. One year later, he purchased the other half-ownership from a Portland stonecutter named George Webber. Although no longer an owner of the quarry, George Webber was not done with John Neal, or our story.

That John Neal used the granite from his North Yarmouth quarry for his house is well established. Where it was used beyond our subject is not at all clear but we do have some evidence. The Maine Quarrying Association was formed by Neal in early 1836. Neal also attempted to form the Hollis Granite Company in 1836 but that does not seem to have passed the legislature.

In 1837 Neal and others received a charter for the North Yarmouth Granite Company. Other than the chartering of the company, I cannot find any other records for it. What I did find is a very brief editorial published in the April 2 1838 of the Eastern Argus that, although quite biased, is enlightening.

“We owe individuals $78,000 – the surplus revenue taken from the pockets of the people, which must be refunded to them, $34,000 – site for the Exchange and granite contracted for with John Neal“

The Exchange

The Merchants Exchange is an odd piece of Portland history. Often called the ‘Custom House’, which it housed for a time but was never officially named as such, its creation was something of a comic opera. Originally conceived by the Board of Trade, of which John Neal was an active member, it was intended to lure the state government away from Augusta and back to Portland. This attempt, and several others that followed over the next century, did not bear fruit. The Exchange stood on the lot between what are now Exchange and Market Streets and faced Middle, where 2 versions US Post Office later stood and is now Post Office Park.

The program was under financed and oversold from the beginning. In 1837, the city government voted, against the advice of many, to purchase the incomplete structure and see construction through to its finish. The stone cutter contracted to finish the building was, you guessed it, George Webber. he was advertising heavily in the local papers in 1837/8 looking for stone cutters and ‘hammerers’ for “immediate hiring” and “good wages”. This gives us some context for the afore mentioned quote. In his auto-biography, Neal states that the granite from his North Yarmouth quarry was not of the quality or quantity needed for the job. A quarry in Kennebunkport, the ‘United States Quarry’, was used. In 1848, the US Government purchased the Exchange. It was destroyed by fire on January 8, 1854.

Meanwhile, on State Street, John Neal had big plans. He initially planned on 8 units each measuring 26.5′ x 110′. He, according to his autobiography, had investors who would pay $300 for a unit. All the units would have the same exterior with the interiors finished to the buyers specifications. Planning and preparation took place in 1835 but, by the time things were ready to begin construction, the Panic of 1837 took place which caused a couple of investors to fail. Neal also claimed that a couple of his so-called investors “jumped ship” to the contemporary Park Street Row. This left Neal to build only 2 of the planned units. John Neal had nothing good to say about the Park Street Row. He claimed it was built using his design. While this may be true, I do not see the connection, he had worse to say.

“substituting brick for granite, and wooden cornices for copper, and shingles for metal and zinc, whereby they saved a few hundreds and succeeded in producing a huge, unsafe, unsightly row of tall houses which passed then, and still pass for a factory.”

John Neal was an active real estate investor/developer for most of his adult life. We have looked at 2 of his projects, on Salem & Mechanic Streets, previously. His name appears some 270+ times in the registry of deeds records for Portland alone. They range from rapid turnover to full on development and cover residential & commercial works.

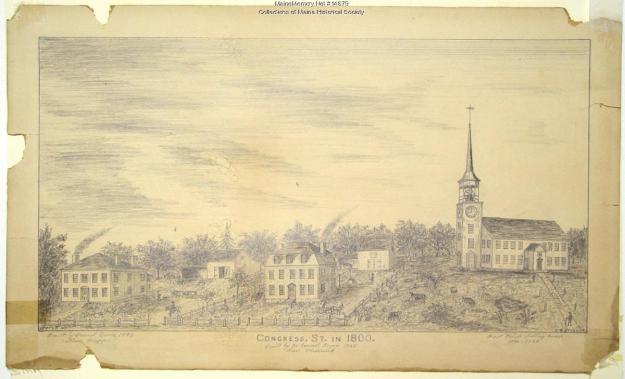

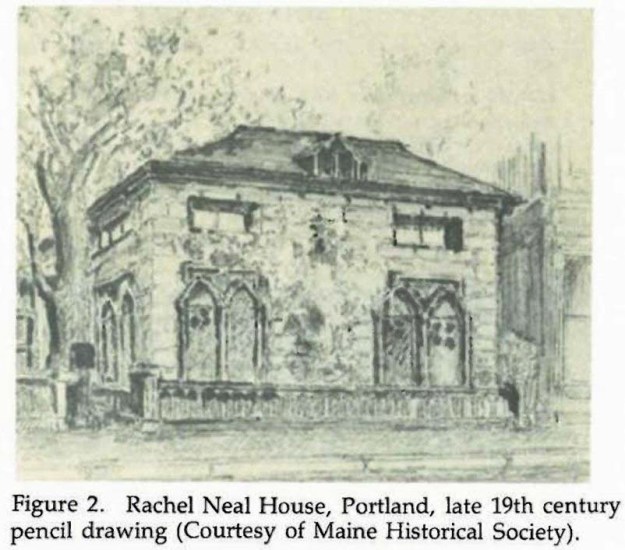

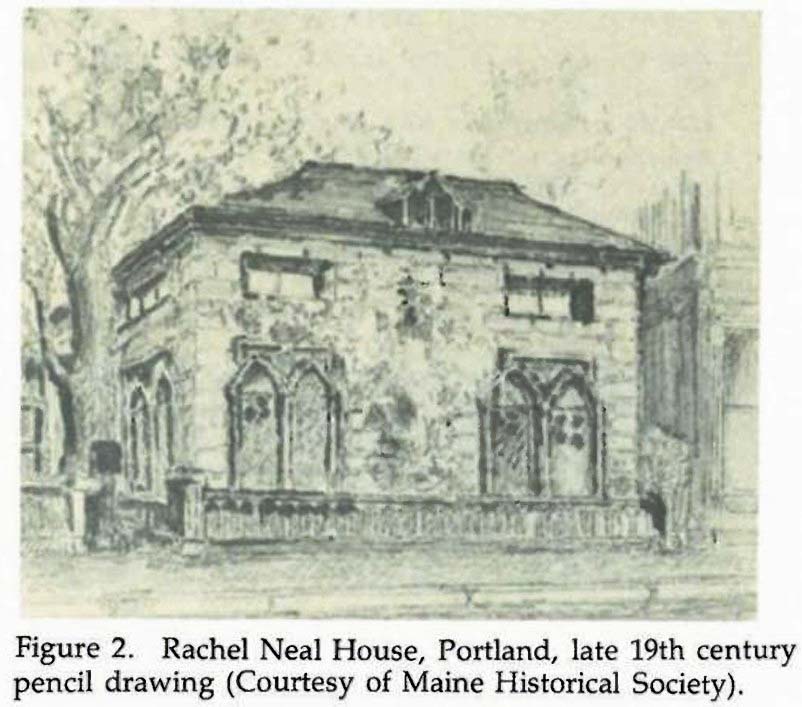

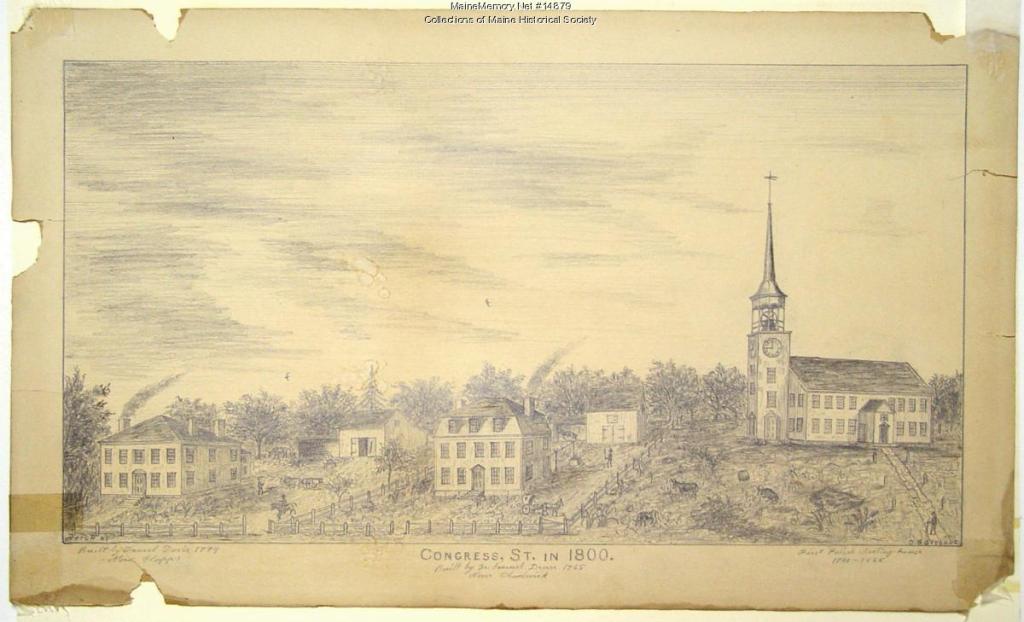

An item of interest is a small stone cottage/house Neal built, presumably for his mother, on Congress Street approximately where Geno’s Rock Club is today. There are few records beyond mention in a mortgage given to Julia & James Furbish in 1839 and a pencil drawing, seen above, now at the Maine Historical Society. The drawing shows a square, two-story, building with a hipped roof and an oddly styled dormer. Perhaps the single most intriguing detail was the Gothic arches over the windows and doors. As the historian William Barry noted:

“Neal deserves credit for creating the city’s first Gothic Revival cottage and advancing that soon to be popular style”

John Neals ‘stone cottage’ was demolished in 1887 or 1888 to be replaced by a house for Dr James Spalding. The house, designed by John Calvin Stevens, was said to have incorporated part of a wall and granite from the previous building.

Cast Iron

173-175 State Street was built in an era that celebrated cast iron. It was an early item to see mass production. Smaller parts could be combined in different ways to create various patterns and designs. John Neal likely created all the designs we see here today. Replete with keys and anthemions , it is a tour de force of Greek Revival motifs. It is a wonder it has survived 190 years and events that could have seen it removed.

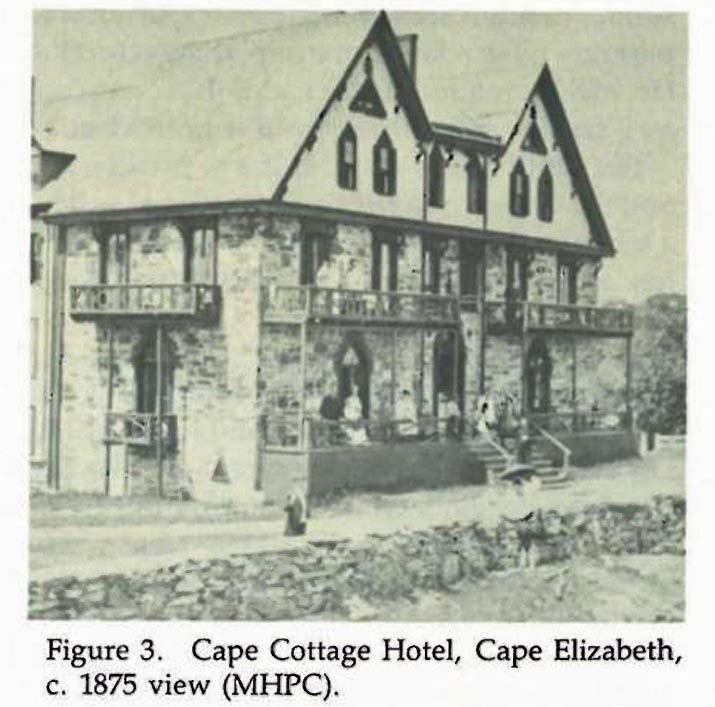

The Cape Cottage

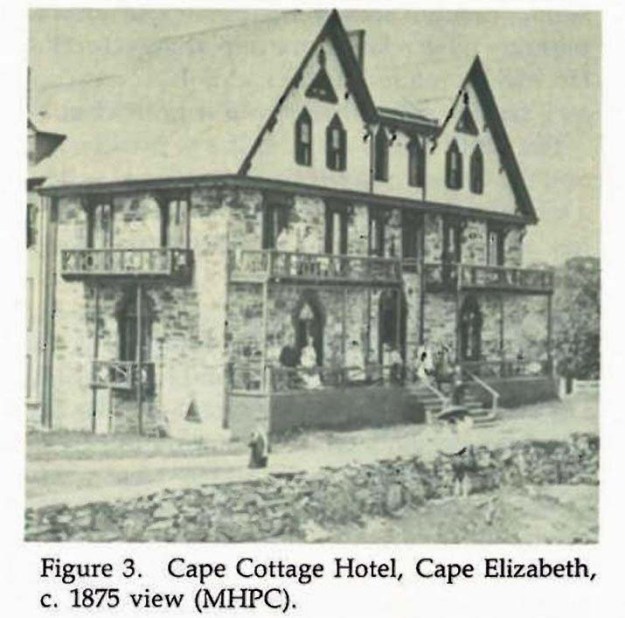

In Cape Elizabeth, John Neal ventured into unchartered territory with the Cape Cottage Hotel. The original hotel was built in 1835-36 and was called Acadian Grove. By 1837, the name had become The Cape Cottage and it was already becoming popular with early ‘rusticators’. The owner of the land on which it was built, Anthony Strout, granted a mortgage to the hotel developers. He sold the mortgage note to John Neal in 1837 and by 1840, Neal was the majority owner. John Neal did not operate the hotel. He leased it to various people during his ownership.

After a fire in 1847, the hotel was rapidly rebuilt only to be completely leveled by another fire in 1849. The replacement of this second structure was again of John Neal’s own design. Here he again dabbled with the Gothic Revival although, by this time, it was more commonplace in the area. He also utilized stone, local fieldstone, in the structure as he had done before for himself and his mother. This was the last time that he built to his own design. In 1853, John Neal sold the Cape Cottage Hotel and it’s grounds to John Goddard. Goddard hired Portland’s ‘starchitect‘ of the day, Charles A Alexander, to design his stone ‘cottage’ that is now an iconic part of Fort Williams Park.

John Neal had better luck selling the second of his two houses on State Street than the Proprietors of the Park Street Row did. He did not have to resort to auction or repeated advertisements to find a buyer in January of 1837. The buyer was a provision dealer, and partner in the North Yarmouth Granite Company, named Daniel Winslow. His surname leads me to believe Daniel was probably a relative of John Neal. Winslow paid $10,000 for the property. The Neals lived in what are today 175 and the Winslows in 173.

The rear of our subject houses is a fascinating thing in and of itself. It is made of brick that would have been whitewashed and is now painted. The placement and size of the windows is functional and not driven by aesthetics. The second floor windows are exceptionally tall and narrow. This tell us that that floor has high ceilings and would have been the primary living level for the houses. The next level would likely have been bedrooms for the family but those may have been on the floor above. The Neals had live in domestics and they were probably housed in the garret. The niches between the windows don’t seem to have a function. The first floor niches may have been for stoves which is possible for the units between the tall windows of the second floor. A head scratcher to be sure.

The porch behind 175 State Street is a slightly quirky bit of the rear facade. Although it is certainly not original, I have to wonder if this replaces an earlier, smaller, structure. It is behind the Neal’s townhouse only although, as seen now, it extends beyond the end of 175 and smashes into the back of 177. It has a vague stylistic connection to the front of 175 but not what we see here on the back. It is not shown on the 1882 tax map but it may have been overlooked. It was here in 1924 and is listed as a ‘sun porch’. Overall, the evidence would suggest John Neal didn’t add a ‘sunporch’ during his time here but, I have a feeling that John Neal was quirky enough to build something such as this.

Daniel Winslow sold 173 State Street to John Neal in 1848 and moved to Westbrook. The following year, Neal sold it to an attorney born in Parsonsfield named Lorenzo De Medici Sweat. Sweat was born in 1818. He and Margaret Mussey were married in October of 1849 a few months after Lorenzo had purchased our subject.

John & Eleanor Neal continued to live at 175 State Street through the 1850s and 60s while John pursued his numerous vocations/avocations in Portland and beyond. As early as 1839, Neal had spoken for women’s equality & suffrage. He was also a staunch abolitionist. He constructed a building for his office on Exchange Street near Fore that was lost in the July 4, 1866 inferno. It would have been near the middle ground of the image below. He rebuilt and that building now houses D. Cole Jewelers. He claimed to have lost “my office and it’s contents, two dwelling houses, a five-story brick mill, and two large warehouses” to the conflagration. He wrote an account of the events of that day which was published in 1868. Neal’s aptly named memoirs, ‘Wandering Recollections’ were started just after the fire and contain several descriptions of rebuilding.

John Neal died on August 25, 1876 at the age of 82. Eleanor followed on December 14 of 1878. At that time, the heirs sold 175 State Street to the Sweats. They rented it a colonel in the Army Corps named Charles E Blunt. Blunt was stationed in Portland to oversee lighthouses along with river and harbor improvements in Maine & New Hampshire. He lived here with his wife Penelope and their adult daughter, Evelina. The city directory for 1882 has the Sweats living on the corner of State and Spring Street, the Blunt family was living in 175 and 173 was occupied a soap maker named Charles Gore.

By the 1890s, both 173 & 175 State Street had become rooming houses. The 1895 city directory and 1900 census show them being operated by a widow originally from Vermont named Sarah J Glover. It’s not clear that she owned them. The 1900 census showed Sarah living in 173 with 10 ‘roomers’ and 6 servants in the 2 units combined. The ‘roomers’ were mostly bankers along with a nurse, lawyer, and the treasurer of a water company. 1910 saw the Hebert family running the houses. A deed from 1915 shows Annie & Sophie Hebert purchasing 173 State Street from Joseph Short. The sisters would have been 8 & 15 years old respectively at the time. The 1924 tax listing has the sisters as owners along with 177 State Street. They have been rooming houses, then apartment buildings to this day.

173-175 State Street are listed as 5-10 family apartment buildings respectively. The condition is good.

If you like what you just read, Buy Me A Coffee!

Thanks for covering the John Neal Houses! I really appreciate the research. And thanks for the compliments on the John Neal Wikipedia article. I rewrote that a few years ago to what it looks like today.

I’ve been researching Neal for years, so I have a few reactions to share after reading through this article. – I haven’t seen anything about Neal working for his uncle James Neal or about James owning a shop on Exchange Street. My understanding is that, at age 12, John Neal first worked for Munroe & Tuttle at Middle and Union Streets, later Benjamin Willis in Haymarket Row, later Charles Atherton’s counting room on Long Wharf, and later George Hill on Union Street. I pieced that all together from Neal’s autobiography, plus the 1972 biography by Benjamin Lease, the 1978 biography by Donald Sears, and the 1933 Harvard dissertation by Irving T. Richards. – My understanding is that the land upon which Neal built these houses he inherited from Uncle James. In the Cumberland County Registry of Deeds book 126, pages 525 and 527, there’s an 1823 plan for that area that marks a sizable portion of land on the corner of State and Maine (now Congress) Streets as “sold to James Neal $995”. These houses take up a fraction of that larger lot. – Daniel Winslow is indeed Neal’s cousin. Their mothers were sisters. Richards includes that in his dissertation. – Your article raises questions about the interior layout of these houses. Neal’s contracts with the builders are held at the Registry of Deeds. Assuming the builders followed the detailed instructions in those two contracts, those instructions provide a fine overview of how each floor was originally laid out. Look for book 143, page 318, as well as book 143, page 395. Those contracts might answer the questions you raised here. – Your article classifies Neal as “a staunch abolitionist.” Neal demonstrated throughout his life that he never supported the institution of slavery, but at the same time he never identified with the abolitionist movement. For a summary of this sentiment in his own words, see the first paragraph of page 403 of his autobiography. He was always in favor of plans for a gradual end to slavery, paired with repatriation of Black Americans to Africa, per the mission of the American Colonization Society, of which he was a longtime vocal supporter. Neal was comfortable with holding radical positions on other issues like women’s rights, but on the subject of slavery, his views were pretty mainstream and thus less admirable from a modern perspective. – Oh, and there are a few 20th-century dates in this article that are clearly meant to be 19th-century: 1936 instead of 1836, and the like. A control-F search for “19” will reveal all of those typos.

Again, thank you for this and other articles on this blog. –Dugan Murphy

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Dugan

Thanks for the insights. I have fixed the date issues. Things like this are why I try to read the text 3 or 4 times before publishing and even then I miss things. I guess that’s what proof readers are for.

I found Neal’s writing to be difficult to read. I endeavored several times to take it on his autobiography but was unable to complete it. In hindsight, I could have left most of the biographical information out and the article would still work. That being said, I think it best to leave the text as written so as to keep your comments relevant.

Your reference to the construction contracts at the registry of deeds was a real eye-opener for me. I have to admit, I had paid little attention to ‘Miscellaneous’ entries prior to reading your comment. To my own detriment it would seem. I have already located contracts regarding a larger project I am working on. I really appreciate that bit of knowledge.

I do thank you very much for your comment and insights. Hearing from local knowledge holders is one of the benefits of this work. I do hope we can keep in touch and, perhaps, collaborate on something in the future.

Thanx for the coffees!

LikeLike

Definitely keep in touch. I love talking about history. I lead historical walking tours during the warmer months, so get in touch if you’d like to join one. My operation is called Portland by the Foot.

LikeLiked by 1 person